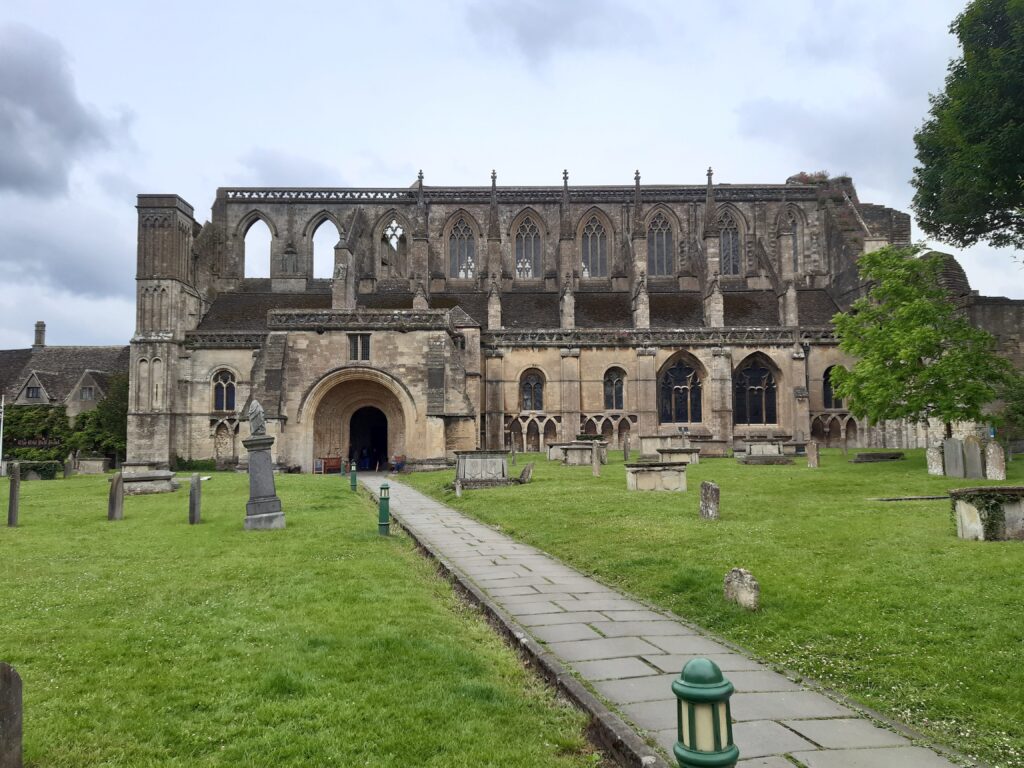

One of the oldest civilising establishments in what became the English-speaking world was Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire (photo of the Abbey illustrates this blog). It is towards the south west of England, in Old Wessex as once was. Established from 676, it bore Christian values through several generations of ambivalent response to those values in the Wessex ruling families.

After two hundred years, however, the ruling family of Wessex truly saw the Christian light. That family’s most famous figure was to be King Alfred the Great, ancestor of today’s UK royal family. Many of Alfred’s family had strong Christian commitment. The family founded England as the after-product of rescuing and restoring Christian Identity in its people.

The actual founder of England was the royal figure most associated with Malmesbury, King Athelstan. He was Alfred’s grandson, mentored by Alfred’s daughter, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians. The dramatic – and uplifting – history of Alfred via Aethelflaed to Athelstan is covered at more length in my book, “The Mustard Seed”.

Anyway, I visited today’s version of Malmesbury Abbey during the time when I was researching and writing my book. Once inside, I was greatly moved, as if by the monks at Malmesbury calling out from long lost bygone times: “Tell Our Story”.

Now, the dead monks of Malmesbury were not speaking to me. Rather, it was a passion becoming articulate in my own heart. And here is what “Tell Our Story” meant at that moment: “They think us monks were just a bunch of Religious Ritual Merchants. But we were the genuine article in Christ. We were Life from the Dead. Tell Our Story.”

We caricaturise Christian monks these days. We have absorbed Post-Reformation propaganda as gospel truth: that the monks were privileged when the many were downtrodden, securely tenured when the many were at the mercy of fickle masters, and they were fat when the many were thin. They copied Bibles because they had nothing better to do; and the Bibles were in Latin, for the clerics only: closed to the Great Unwashed.

By Protestant Reformation times (1500’s), there would have been some truth in it. King Henry VIII, initiator of the Reformation in England, and much maligned in modern times, was a liberator when he insisted that every church must display a copy, in English, of the Bible for as many to read in their own language as could read it. However, there was also a need to vindicate the re-distribution, which he had set in motion, of the monastic wealth to the court favourites. I think we can safely say that the caricature of the monks arose from propaganda to vindicate that. And it has blinded us to the more noble legacies of the earlier Christian monks.

An all-time-great amongst them was St Martin of Tours, 316-397. I cover him at length in my book, “The Mustard Seed”. There is a little about him in blogs on this website too. He had what a modern Christian would call revelatory and miraculous Life in the Holy Spirit of the Christian God. As the 600’s went on, pagan Anglo Saxon kingdoms embraced that type of Christian witness one after another. The movement came into the South and East of what became England mainly via Christian Franks. Their starter Saint and hero? – St Martin of Tours. It came into the North and Midlands of England via those trained in the ways of Celtic Iona and of Lindisfarne. Their starter Saint and hero? – St Martin of Tours. My book shows you the process. The point to make here is that I reckon that St Martin would be given the stage today at those churches in the western world which want to teach their people how to live in the revelatory and miraculous realms of Christian Life.

Martin’s powers seem to have descended to other notable monks after he died. St Patrick, once you penetrate behind the legends, became one of history’s greatest examples of a Christian living out Christ-patterns. Prior to that, he sought out the spiritual legacy of St Martin with all his heart. Both Patrick, in 432, and the monk St Augustine of Canterbury, in 596, were empowered for their world-shaping missions to bring Christian Awakening to pagan peoples at the same centre, monastic Lerins. St Martin had made a point, in later life, of training the keen Christian young of Europe, as they became monks, to emulate his Life in the Holy Spirit of the Christian God. It was one of his trainees, St Honoratus, who set up monastic Lerins.

St Patrick was most likely initiated into Christian Life as a young man out of monastic life set up by St Ninian. St Ninian had encountered the then-aged St Martin before 397. Ninian also spent time at Lerins, after that, before setting out on Christian mission to what we now call Scotland. Again, you can rediscover Ninian in my book.

Anyway, here is the point about these monks. They sacrificed much for their Christ. Patrick went to those who had once enslaved him. Augustine left behind greater comfort. Ninian ventured to frontier territory. As for Martin, his life was not his own.

A key spiritual descendant of St Martin – via Saints Ninian, Patrick and Columba – was the monk St Aidan, of Lindisfarne fame. He ministered in what was then called Northumbria (North East of England plus Scottish Borders) between 635 and 651. He walked amongst the people bringing Christian light. He also trained a fuller team of monks. These later brought Christian light into Mercia (Midlands of England) and London. Northumbria and Mercia had been warrior-to-the-bone rivals for un-numbered generations, first in the Germanic homelands, later in what became England. Aidan and his team, plus others later coming out of York, initiated the two warrior powers into shared Christian Identity. That became their chief common value. In 679 the great Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury brought them to peace on that foundation – nation shaping, world history shaping.

St Aidan’s successor after 651 was the monk, St Cuthbert. Like Aidan, he walked amongst the people bringing great goodness. But later, he retreated to a life of prevailing prayer as a hermit on a tiny island. From that island, and also after his death in 687, as you can read in “The Mustard Seed”, he impacted national and world history. Cuthbert was a phenomenon, as near to the powers in Christ and in the Old Testament prophet Elisha as you could get, I should say. In his lifetime, he had a rather contentious rival, one Bishop Wilfrid. It would have been to avoid contentious spirit that Cuthbert went into his hermit retreat. You can read about both these figures in my book and about Wilfrid in the blog “Easter Dating”. Wilfrid was a Colossus of the Christian Church. The monk Cuthbert was a Colossus of Life in the Holy Spirit of the Christian God. They each interacted with another Colossus, Archbishop Theodore, lost nation-shaper, lost apostle. The point to make here is, that out of all of them, in terms of spiritual legacy enduring even down to this day, Cuthbert, hermit monk, was the winner. I explain in “The Mustard Seed”. However, long story short, the Life in the Holy Spirit of the monk, St Cuthbert, brought generationally enduring goodness into the Western world. Out of self-exile on a tiny island.

Then there was Athanasius, early 300’s, broadly. Another monk. Embedded in his writings seem to have been the powers of a Billy Graham of his time. His written work catalysed the later-life spiritual empowerment of St Martin of Tours. Athanasius was also a rescuer of Christian truth from Arian doctrines which, left unchecked, would have destroyed the Christian witness of the Early Church. Comfortable monk? More like a life-risking one. Athanasius doesn’t get into my book, except one small mention. A further blog may look at him some time.

The point for now: these early monks were not privileged, secure and fat. Although they did have one privilege, as they themselves would have reckoned it: the privilege of knowing the Christ within. Out of that, they gave up all they had to serve their Christ in lives of deprivation and devotion. The many monks who descended from them did not copy Bibles because they had nothing better to do. They copied Bibles as the Word of Life. And they didn’t set up Controlling Church, as is the fashionable modern accusation. The Christian Life within them intertwined with a Nation of the English which freely chose to intertwine with it. In so doing, it shaped our world from their times to our own.

There is a word in Christian circles which defines a particular calling: Apostle. It means, Sent One. These monks and many others became an Apostolic movement – corporately, the Sent Ones. That is the Story which, in Malmesbury Abbey, I felt impelled to Tell.

Now, my book, “The Mustard Seed”, is not devoted to that as the central story. It more generally shows how Christian Identity shaped real world Anglo Saxon and Early English history. However, the vibrant spiritual legacy of the early monks, seen through an eye which does not have the usual squint of Post-Reformation propaganda, is an extra that you will find emerging from the book.